Exploring the relationship between food and culture reveals how what we eat shapes identity, memory, and social life across generations. This article delves into culinary traditions, rituals, and global exchanges to show why food is more than sustenance — it is a language, an archive, and a force for change. H2: The Role of Food in Cultural Identity Food is a cornerstone of cultural identity, anchoring people to place, history, and community. Traditional dishes act as edible archives, preserving ingredients and techniques passed down through families. When someone says they “eat like their grandmother,” they are referencing an entire matrix of taste, memory, and lineage that helps define who they are. H3: 1. Historical RootsMany culinary practices have deep historical roots tied to agriculture, trade, conquest, and migration. For example, the introduction of chili peppers to Asia and Europe after the Columbian Exchange reshaped cuisines across continents. These shifts show how food evolves while carrying traces of older histories. Over time, historical influences become normalized and embedded. A dish that once marked foreignness can become emblematic of national identity — consider how tomatoes, once exotic in Europe, became central to pasta and pizza. This demonstrates how food histories contribute to evolving cultural narratives. H3: 2. Festivals and RitualsFestivals turn food into public ritual. Seasonal celebrations, religious fasts, and life-cycle events (births, weddings, funerals) all use specific foods to mark meaning. In many cultures, the same dish prepared annually functions like a seasonal bookmark that binds the present to the past. Ritual foods often carry symbolic layers: fertility, purity, remembrance. These layers offer communities a shared vocabulary. By participating in culinary rituals, people enact membership and continuity — a powerful expression of cultural identity. H2: Food as Language: Communication and Social Meaning Food communicates values, status, and relationships. Sharing a meal signals trust; the order and nature of dishes can indicate respect, hierarchy, or intimacy. Culinary etiquette is part of the grammar of social life. H3: 1. Hospitality and Social BondsHospitality is universal but expressed differently. In Middle Eastern cultures, offering coffee or dates can be a formal gesture of welcome; in East Asia, sharing several communal dishes emphasizes harmony and group cohesion. These practices are not merely niceties — they are essential systems that create and sustain social bonds. Over time, hospitality rituals become habitualized into social expectations. Refusing food can be interpreted as rudeness, and accepting food confers acceptance into the group. That dynamic makes food a subtle yet powerful social currency. H3: 2. Symbolism in Ingredients and DishesIngredients often carry symbolic meanings. Rice can symbolize life and prosperity in many Asian cultures; bread has sacramental value in Christian traditions; fish can represent abundance or spiritual meanings in different contexts. These associations are taught and reinforced through storytelling, religion, and everyday practice. Symbolic foods can also be tools of resistance or identity affirmation. Diaspora communities may emphasize certain dishes to maintain ties to a homeland, while marginalized groups might reclaim foods to assert cultural dignity. In all cases, food functions as an ongoing conversation about who we are. H2: Globalization, Migration, and Culinary Exchange Global flows of people and goods have accelerated culinary exchange, leading to creative fusion and contested debates about authenticity. Migration and trade make local tastes porous, creating delicious hybrids and raising questions about cultural appropriation. H3: 1. Fusion Cuisine and Authenticity DebatesFusion cuisine exemplifies innovation: sushi burritos, kimchi tacos, and Indo-Chinese stir-fries are examples where traditions collide productively. Yet fusion can provoke debates over authenticity. Critics ask: who has the right to adapt a dish, and at what cost to its origin community? These debates often hinge on power and representation. When big restaurant chains adapt dishes without credit or fair economic benefit to origin communities, tensions arise. Conversely, thoughtful fusion can create new traditions that respect roots while embracing change. H3: 2. Diaspora Communities and Food PreservationDiaspora communities preserve culinary memory as a way to maintain identity. Ingredients may be substituted when originals are unavailable, giving rise to creative adaptations. For example, immigrant cooks often replicate dishes with local produce, producing regionally distinct offshoots of the original cuisine. Food also becomes a medium for storytelling in diaspora life. Family recipes transmit language, history, and emotion. Through food, diasporas negotiate belonging in host societies while keeping ties with ancestral homelands. H2: Food Policy, Economy, and Sustainability What we eat is shaped by markets, policies, and ecological constraints. Food systems influence cultural practices and vice versa: subsidies, globalization of supply chains, and climate change all shape culinary futures. H3: 1. Food Security and Cultural DietsFood security policies must acknowledge cultural diets. Importing calorie-rich, nutrient-poor processed foods can undermine traditional diets that are healthier and culturally meaningful. Policy decisions about what crops to subsidize have ripple effects on culinary practices and nutritional health. Addressing food security therefore requires culturally informed strategies: supporting local crops, protecting smallholder farmers, and promoting traditional foodways that align with health and identity. Culturally competent food policy is essential for resilient communities. H3: 2. Sustainable Food Practices Rooted in TraditionMany traditional food practices are inherently sustainable: crop rotation, mixed farming, fermentation, and foraging have low environmental footprints and high nutritional value. Reviving and scaling these practices can aid contemporary sustainability efforts. For instance, community seed banks help preserve crop diversity and cultural heritage. Similarly, traditional fishing or agroforestry methods can offer models for climate-adaptive food systems. Connecting modern policy with traditional knowledge is both practical and respectful. H2: Preserving Culinary Heritage and Future Trends Culinary heritage preservation involves documentation, education, and thoughtful commercialization. Simultaneously, technology and media are transforming tastes and access, creating new possibilities and challenges for cultural continuity. H3: 1. Documentation, Education, and TourismDocumenting recipes, oral histories, and foodways preserves intangible heritage. Museums, cookbooks, and culinary schools play roles in safeguarding traditions. Food tourism can support local economies but risks commodifying culture if not managed sustainably. Best practice balances economic benefit with community control. Initiatives that empower local cooks, ensure fair compensation, and foster authentic exchange help transform tourism into

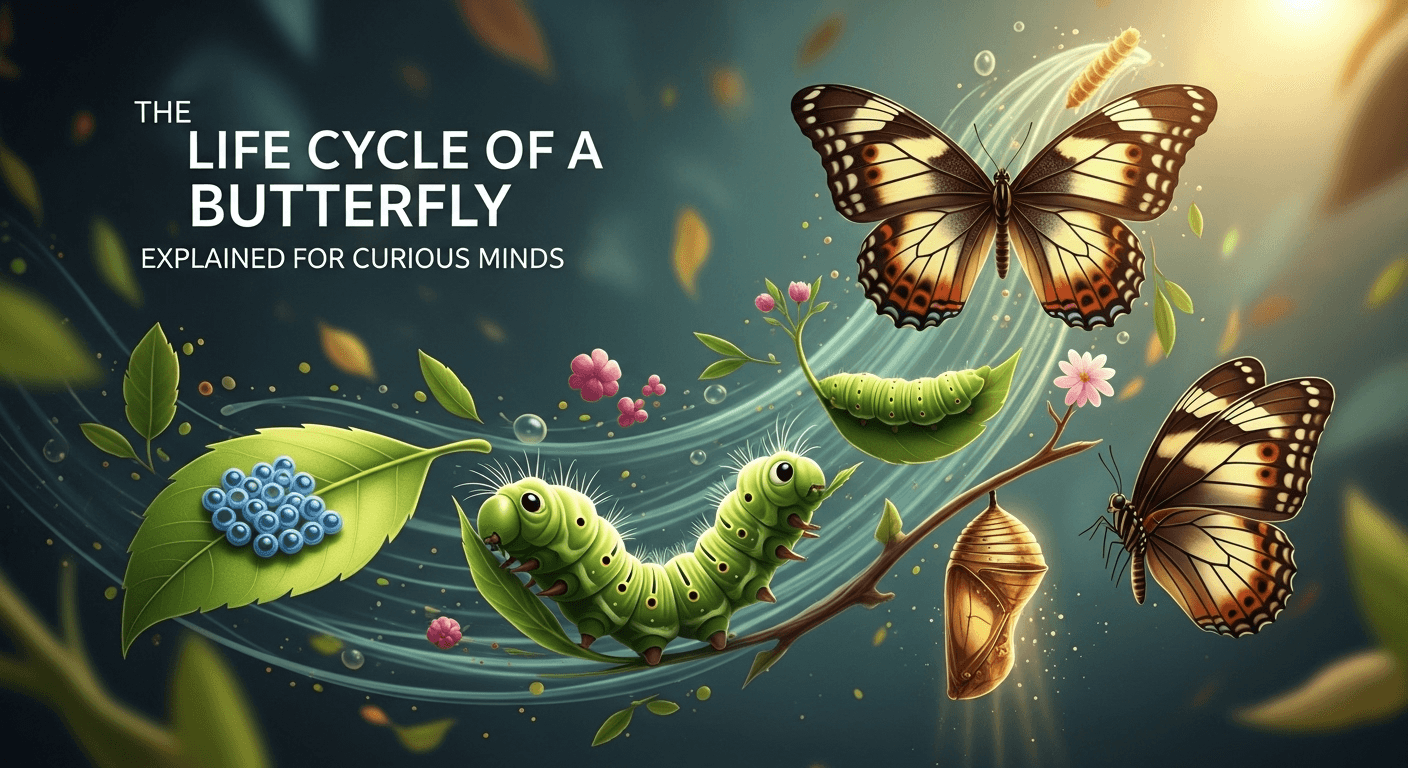

The Life Cycle of a Butterfly Explained for Curious Minds

Curious about how a delicate winged insect transforms from a tiny dot on a leaf into a graceful pollinator? You’re in the right place. In this guide, you’ll find the life cycle of a butterfly explained in a clear, engaging way that blends science with stories from the garden and field. Whether you’re a student, teacher, home gardener, or nature lover, you’ll learn how each stage works, how long it lasts, and how to support butterflies in your local environment. Butterfly metamorphosis is one of nature’s most dramatic transformations. Yet, it isn’t magic—it’s biology at its most elegant. From egg to caterpillar to chrysalis to adult, each stage is laser‑focused on survival and reproduction. Read on for The Life Cycle of a Butterfly Explained for Curious Minds, and discover how timing, temperature, plants, and predators shape the journey. Understanding Butterfly Metamorphosis Metamorphosis is the multi-stage transformation butterflies undergo to mature into adults. Butterflies are holometabolous insects, meaning they experience a complete metamorphosis with distinct body plans at each stage. This separation of form and function allows them to exploit different habitats and food sources throughout life, which helps reduce competition—and boosts survival. In everyday terms, think of it like a four-part series with entirely different sets: egg (setup), caterpillar (resource gathering), chrysalis (transformation), and adult (reproduction and dispersal). Each stage is optimized to perform its role exceptionally well, even if the creature looks and behaves totally differently than it will in the next chapter. To fully appreciate this process, it helps to know some basics: most butterflies are tied to specific host plants; temperature tightly controls growth rates; and parasites, predators, and weather shape which individuals make it to adulthood. Those forces guide evolution—and your chances of seeing butterflies in your yard. 1. What Is “Complete Metamorphosis”? In complete metamorphosis, the larval form (the caterpillar) looks nothing like the adult. Inside the chrysalis, larval tissues are broken down and reorganized into adult structures such as compound eyes, antennae, wings, and reproductive organs. That deep remodeling is possible thanks to specialized cells and hormonal signals that coordinate growth and timing. This strategy lets caterpillars specialize as eating machines—stockpiling energy—while adults specialize in dispersal and mating. Because larvae and adults don’t eat the same foods or compete for the same resources, the species can occupy broader niches, a major evolutionary advantage. 2. Why Butterflies Evolved Metamorphosis Metamorphosis likely evolved as a way to split life tasks between two body types. A soft-bodied, camouflaged caterpillar living on leaves faces different threats than a flying adult with bright colors and a long proboscis for sipping nectar. This division-of-labor reduces intraspecific competition: babies eat foliage; adults roam widely to find nectar and mates. Evolution also favors flexibility. As climate and habitats shift, a life cycle with multiple distinct stages can adapt through changes at one stage without breaking the whole system. For example, if spring arrives earlier, eggs can hatch sooner and caterpillars can feed during the new leaf flush. Stage 1: Eggs and Embryonic Development Butterfly eggs are tiny marvels—often only a millimeter or two wide—with shells sculpted in delicate patterns. A female typically lays eggs on host plants that her species’ caterpillars can digest. Host plant choice is crucial: it decides whether the hatchling will have immediate access to food and the right chemical cues. Egg color, texture, and placement vary by species. Some butterflies lay single eggs on leaf undersides to hide them from predators, while others lay clusters. Temperature and moisture influence development speed; warmer conditions generally speed things up, within safe limits. Survival at this stage is a numbers game. Many eggs never hatch due to predation by ants or wasps, desiccation during hot, dry weather, or being laid on leaves that are later eaten or blown away. That’s why many species lay dozens or hundreds of eggs over a lifetime. 1. Choosing the Right Plant Female butterflies use sight, smell, and touch to choose a host plant. With their feet—yes, their feet—they can “taste” plant chemicals to confirm the match. For instance, the monarch, Danaus plexippus, relies on milkweeds (Asclepias spp.) whose compounds later help protect the caterpillar and adult from predators. This plant–insect partnership is the backbone of successful development. If the host is absent or treated with pesticides, eggs may be wasted and larvae starve. Gardeners who want to help butterflies should plant region-appropriate host species and avoid systemic insecticides that linger in plant tissues. 2. Inside the Egg Inside the shell (chorion), embryonic cells divide and differentiate. Rudimentary segments and head structures appear, and the embryo consumes the yolk for energy. By the end of development—often within 3–8 days in warm weather—the tiny caterpillar is ready to chew its way out. When hatching, many caterpillars eat the eggshell, a protein-rich first meal that jump-starts growth. This thrifty behavior recycles nutrients and leaves fewer traces for predators. 3. Threats to Eggs Eggs are vulnerable to extreme weather, drying winds, heavy rainfall, and UV exposure, depending on where they’re laid. Predators like ants, lady beetles, and tiny parasitic wasps can decimate eggs before they hatch. To boost survival rates, females may spread eggs across multiple plants and locations. This “portfolio strategy” hedges against localized threats such as a leaf being eaten, a branch breaking, or an area being treated with lawn chemicals. Stage 2: Caterpillar (Larva) — Growth Machine Once hatched, the caterpillar begins the most energy-intense period of its life: eating and growing. Caterpillars are essentially specialized guts on legs—built for consumption and conversion. They eat host plant leaves and convert them into body mass at astonishing rates, often growing thousands of times their hatch weight. Because their exoskeletons don’t stretch, caterpillars outgrow them and must molt several times. Each period between molts is called an instar. Instar count varies by species and temperature, but five instars is common for many. While feeding and growth are the main tasks, survival is an equally important job. Camouflage, chemical defenses, and behaviors such as hiding under leaves or