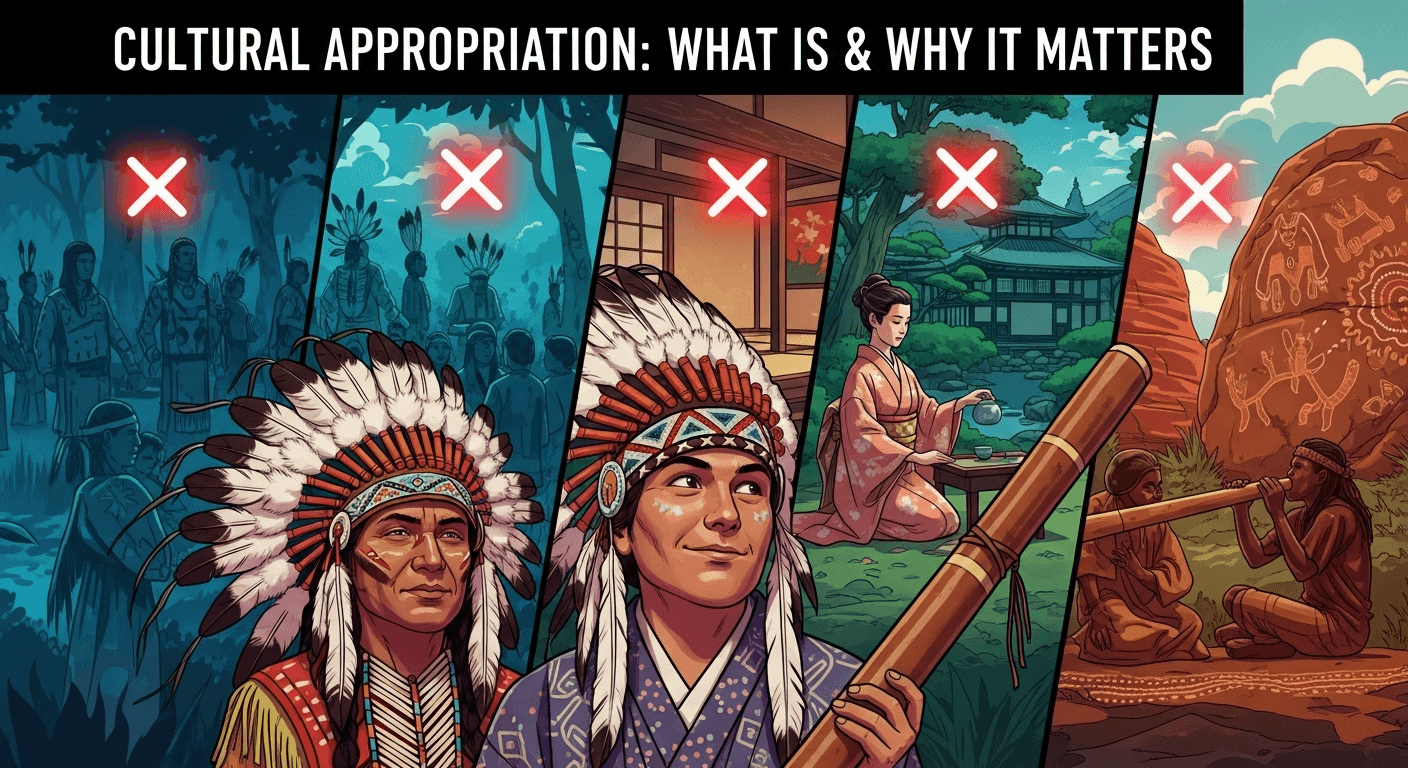

Navigating our increasingly connected world means encountering a beautiful mosaic of cultures, traditions, and ideas. This exchange can be a source of immense learning and unity. However, it also opens the door to a complex and often painful issue. You might see it at a music festival, on a fashion runway, or even in a yoga studio—a non-Native person wearing a feathered war bonnet, a high-fashion brand using sacred Indigenous patterns, or a wellness guru selling "smudging kits." These instances often spark heated debate and accusations of insensitivity. At the heart of this controversy is a critical question: what is cultural appropriation? It’s a term that signifies more than simple borrowing; it describes a dynamic where elements are taken from a marginalized culture by a dominant one, often stripping them of their original meaning and context, and frequently for profit, without understanding, credit, or permission. This article will delve into the nuances of cultural appropriation, distinguish it from appreciation, explore its real-world impact, and offer guidance on how to engage with other cultures respectfully. Cultural Appropriation: What It Is & Why It Matters At its most basic level, cultural appropriation is the unacknowledged or inappropriate adoption of the customs, practices, ideas, or tangible cultural elements (like clothing, music, or art) of one people or society by members of another, typically more dominant, people or society. It’s crucial to understand that this isn’t about creating cultural silos or preventing people from enjoying things from outside their own heritage. The key distinction lies in the power imbalance between the source culture and the adopting culture. When a dominant group borrows from a marginalized or historically oppressed group, the dynamic is fundamentally different than when two groups of equal power exchange ideas. The act of appropriation often involves a process of stripping the cultural element of its original context and significance. A sacred religious symbol, for instance, might be turned into a disposable fashion accessory. A traditional hairstyle that carries deep cultural identity and has been a source of discrimination for one group might become a "cool" trend when worn by someone from the dominant group. This process trivializes practices and objects that may be deeply meaningful or even sacred to the source culture, reducing them to mere aesthetics or commodities. Ultimately, appropriation is not a simple, friendly exchange. It's an act of taking without consent, understanding, or reciprocity. Think of it like this: a friend sharing their family recipe with you is a beautiful exchange. However, taking that recipe without asking, mass-producing it, calling it your own "exotic" creation, and making a fortune from it while your friend's family struggles to keep their small restaurant open is an act of exploitation. Cultural appropriation operates on a similar principle, but on a societal scale, often perpetuating cycles of misunderstanding and economic disparity. The Core Elements of Appropriation To better identify cultural appropriation, it helps to break it down into its key components. These elements often work in combination to create a situation that is harmful, disrespectful, or exploitative. Understanding them allows for a more nuanced analysis of any given situation, moving beyond a simple "is this okay or not?" and into a deeper understanding of the dynamics at play. #### The Power Dynamic: Majority vs. Minority This is perhaps the most critical element. Cultural appropriation is intrinsically linked to power and history, specifically the relationship between dominant cultures (often Western, white societies) and marginalized cultures (such as Indigenous peoples, Black communities, and other people of color). When a member of a dominant group adopts elements from a marginalized culture, they often do so without experiencing the discrimination, oppression, or systemic barriers that people from that culture have faced because of those very same elements. For example, a white person wearing dreadlocks as a fashion statement can be seen as trendy. However, Black individuals have historically faced—and continue to face—workplace discrimination, school suspensions, and social stigma for wearing the exact same hairstyle. The white person can "wear the cool" without "carrying the cost." This selective celebration reinforces a harmful double standard where the dominant culture gets to pick and choose the "fun" parts of another culture while ignoring the lived realities and struggles of the people who created it. #### Lack of Context, Credit, and Significance Appropriation thrives in a vacuum of context. It involves taking a symbol, practice, or style and divorcing it from its original cultural, spiritual, or historical meaning. A Native American war bonnet (headdress), for example, is not a hat. It is a sacred item earned through specific acts of bravery and honor, reserved for respected leaders within certain Plains nations. When worn as a costume to a music festival, its profound significance is erased and it becomes a generic “tribal” accessory, turning a symbol of respect into an object of disrespect. This erasure is compounded by a lack of credit. The appropriated element is often rebranded or presented as something new and edgy, discovered by the dominant culture. The original creators and their generations of tradition are rendered invisible. This isn't just rude; it contributes to the systemic erasure of marginalized histories and intellectual contributions, making it seem as though innovation and beauty only flow from the dominant culture. Giving credit and understanding context are fundamental to respectful engagement. #### Commodification and Profit A major red flag for cultural appropriation is when a cultural element is commodified—turned into a product to be bought and sold—especially when the profits do not benefit the source community. Large corporations and fashion designers often take traditional patterns, sacred imagery, or artisanal techniques from Indigenous or other minority groups, mass-produce them, and sell them for a significant profit, with no compensation or acknowledgment given to the people who originated them. This is not only economically exploitative but also deeply unfair. It allows the dominant culture to profit from the very things for which the source culture has been historically punished or mocked. For instance, fast-fashion brands might sell cheap knock-offs of intricate traditional